FROM NEWSWEEK | OCTOBER 10, 2008

Remember the ownership society? It was a vision woven by President George W. Bush when he was running for re-election in 2004, which saw every American family in a home, and a government that stayed out of the way of the American Dream. The families were, of course, conservative, or at a minimum traditional and nuclear, consisting of a heterosexual married couple and at least two kids living in a stand-alone home with a yard, a car or two and a multimedia room with a flat-screen television. OK, so the latter was a new addition, a 21st-century simulacrum of the 1950s "Leave It to Beaver" idyll. But the dream was the same.

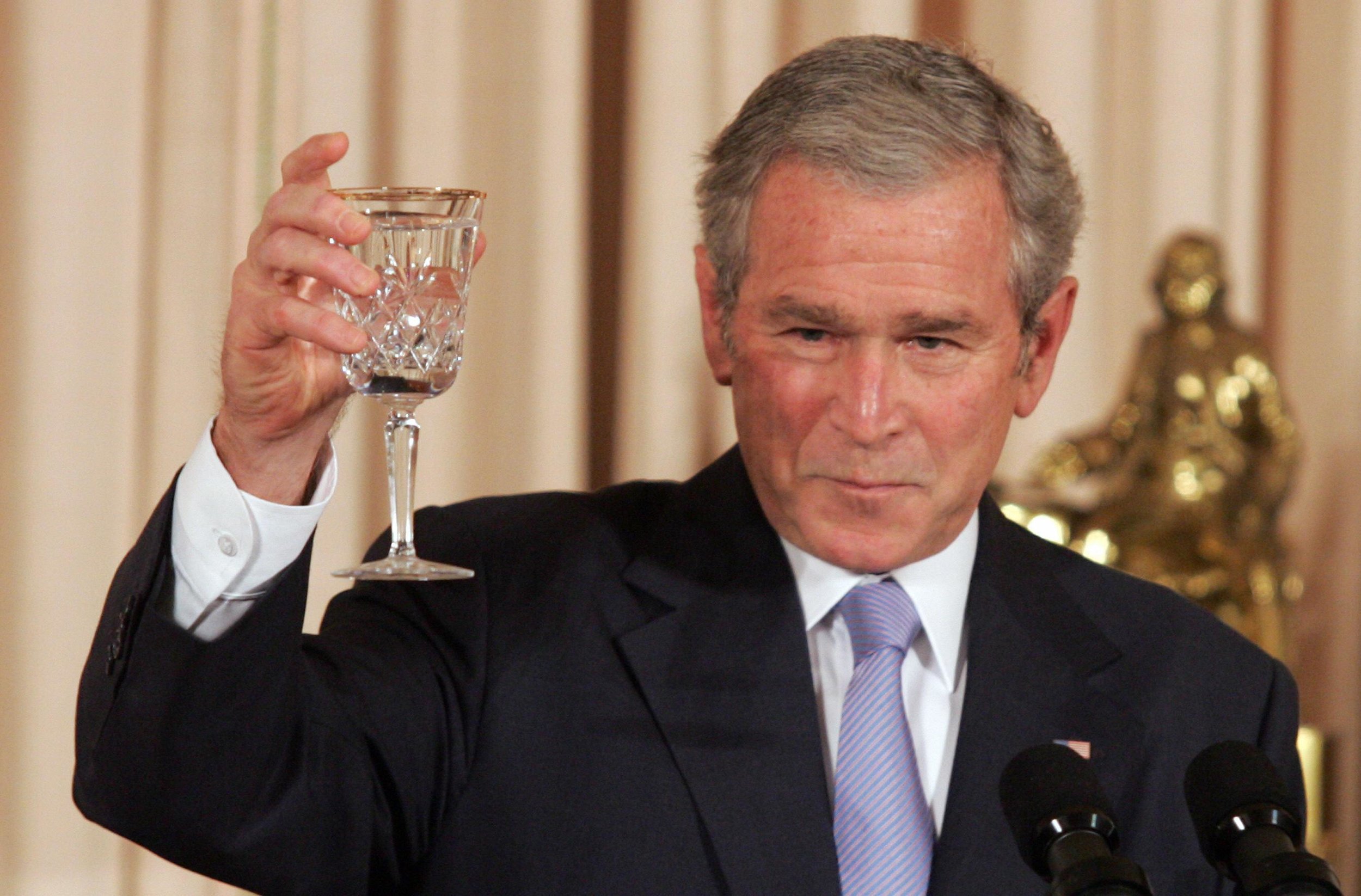

The goal was to secure stability and prosperity, and the ownership dream was the way to achieve that. "America is a stronger country every single time a family moves into a home of their own," said Bush in a speech back in October 2004. To achieve that vision, Bush pushed new policies encouraging homeownership, such as the "zero-down-payment initiative," which was much as it sounds: a government-sponsored program that allowed people to get mortgages with no down payment. More exotic mortgages followed, including ones with no monthly payments for 24 months. Then there were mortgages with no documentation other than the say-so of the borrower. Absurd though this was, it paled in comparison to the financial innovations that surrounded those mortgages, derivatives built on other derivatives, packaged and repackaged until no one could identify what they contained and how much they were in fact worth.

As we all know by now, they've brought the global financial system to an improbable brink of collapse. Ironically, the Bush ownership ideology may ultimately end up having the same effect on the stable nuclear families that conservatives so badly wanted to foster.

The dream of a better society through homeownership didn't originate with George W. Bush. It was as American as Manifest Destiny. The Homestead Act in 1862 offered acres to anyone willing to brave it on the Western frontier. During Reconstruction, freed slaves were promised "40 acres and a mule." But until very recently, those hopes and dreams were connected to actual income and having gainful employment. No longer.

The Bush years built on the promise of the New Economy era that it followed, a promise perfectly encapsulated by a 1999 billboard in Scroggins, Texas, in front of a shining new subdivision filled with homes that most of their buyers couldn't really afford: YES, YOU CAN HAVE IT ALL! That dream took a sharp hit with the collapse of the Internet stock bubble in 2000–2001 and then with 9/11, both of which destroyed billions of dollars of wealth. But it came roaring back in 2002, encouraged by Bush's post-9/11 exhortation that Americans could do their patriotic duty by going shopping and paying lower taxes, even as government spending exploded. Shop they did, and homes they bought.

The spree wasn't confined to the United States. Across the pond, Britain had its own version of the ownership society, which had received a boost from Margaret Thatcher, who had promoted "a property-owning democracy" that her Labour successors, Tony Blair and now Gordon Brown, endorsed. Blair, for example, liked to talk of building a "stakeholder economy" with a big role for the ordinary property-owning citizen. More recently, Brown has spoken of creating a "home-owning, asset-owning, wealth-owning democracy." Millions were happy to buy into the vision that began with Thatcher. Tenants of local authority-owned properties gladly took up the Conservative government's offer to sell them their homes at knockdown prices. More than 70 percent of Britons now own their homes, compared with 40 percent of Germans and 50 percent of French.

In Britain as in the United States, it wasn't just about owning a home. It was about being a better person. With a home came traditional values, an appreciation of hard work, prudent living, civic-mindedness, patriotism and ultimately a more stable society. Or so the rhetoric went.

But eventually, it all went sour. By the turn of the century, the proliferation of easy credit and stock ownership combined to create anything but a conservative society of thrift. Average household debt levels are now higher in Britain than in any other major country in the developed world. In the United States, the shift away from corporate pensions to 401(k) Individual Retirement Accounts plunged millions more into the equity markets and loosened the traditional connection between companies and workers, which was one element of that 1950s dream that conservatives such as Bush conveniently forgot. The ownership society of the 1950s was anchored by a labor movement that made sure that workers received something resembling their share—remember Truman's Fair Deal? The deal for the past eight years has been fair to merchants of capital, and then some, but to the tens of millions on the receiving rather than originating end of those mortgages, fairness has been in short supply.

No, this can't be reduced to a swindle. We all bear some burden for the current morass. You can't peddle what people don't want to buy, and for a while it seemed a decent trade-off: Wall Street got rich, and Main Street got homes. The easy terms—and that is putting it lightly—of mortgages gave many a chance to own a home who never would have qualified for a mortgage in years past. But it also gave others the option to buy, sell and flip. Every speculator a homeowner, however briefly? That wasn't supposed to be part of the equation.

The irony is that more homeownership and stock ownership has actually weakened traditional bonds. For the past decade, as homeownership went up, marriages continued to fail. Fewer people are getting married as a percentage of the population than at the beginning of the decade. Single-parent homes are on the rise. So is unemployment. It has increased to 6.1 percent, up from 4.5 percent in 2000. With foreclosures now at more than 300,000 a month, and stock portfolios and retirement savings shrinking with the global equity sell-off, there has been a notable increase in demand for mental-health services—which is a problem, given that many health-care plans, the ones left to the private sector, cover only a few visits. Studies have also shown a link between difficult economic straits and declining health and higher mortality. Either people need a quick cure, or home prices have to rise soon. Neither is likely. As journalist Tina Brown, a sharp tracker of social trends, recently said at NEWSWEEK's Women in Leadership conference, "I think the financial crisis is going to put a lot of marriages under great stress. There really isn't enough to go around, and there are choices to be made, and particularly husbands, many of them who are in jobs where they pride themselves, their whole ego is invested in the job. When men lose their job they frequently feel a great loss of manly self-confidence, and that has great impact on a marriage. So I think we'll see quite a lot of divorces and separations and very difficult marriage stuff happening."

The final referendum of the vision of the past eight years is, of course, the November election. The rhetoric of both parties and candidates for president suggest that regardless of who wins, the ownership vision is being rejected in favor of hunkering down, paying off debt, regulating the anarchic world of credit and derivatives, and unraveling systemic knots that have assumed Gordian complexity. As Barack Obama said recently, "In Washington they call this the ownership society, but what it really means is, you're on your own … Well, it's time for them to own their failure."

But it would be premature to write the obituary of the ownership society. This crisis will pass, eventually, and on the other side there will still be global electronic exchanges and computer-enhanced models; there will still be mortgages; and there will still be a deep cultural yearning for a place of one's own. There may be less froth and more discipline in the coming years—combined with reduced circumstances and less money. Lean times, however, are their own source of hopes and desires, and drive people to find new ways to satisfy old yearnings. There may be more prudent ways to create a world where families are stable and living in their own homes (see the Robert Shiller piece to follow). But the gap between that dream and messy reality isn't likely to close any time soon. Once the dust settles, perhaps we will have learned something about how much we can have and how quickly. For Americans in particular, that would be a real revolution.